Republican Gov. John Kasich in his office at the Statehouse in Columbus, Ohio (Photo: Joshua A. Bickel for Yahoo News)

It’s a frozen February evening in West Virginia, and John Kasich has gotten sidetracked yet again. For two full days, Kasich, the Republican governor of Ohio, has been wooing local legislators and jousting with the press as he tours Columbia, S.C., and Charleston, W.Va., in support of his longtime hobbyhorse: a federal balanced-budget amendment.

But for now, at least, the traveling is over. It’s time to relax. Kasich and his entourage are about to leave the West Virginia Statehouse. Outside, the governor’s private plane is waiting to whisk him back to Ohio; an aide assures him that there is wine onboard.

The only hitch, as anyone who has ever met John Kasich can confirm, is that John Kasich cannot relax.

“Energy is what drives things,” he will tell me later. “Excitement! Progress! Innovation! Forward! Discover America! Find the Pacific Ocean! Climb the mountain! Chart the course! Change the world! Land on the moon! Go to Mars! I mean, that’s my job. My job is to say to people, ‘Go do it. Go! Go West, young man! But let me know where you are, OK? ’Cause I don’t want to have to send a bunch of people out to save you because you didn’t have a canoe to get across the Missouri River.’”

Photo: Joshua A. Bickel for Yahoo News

This is how Kasich is. His colleagues in Congress — Kasich represented Ohio’s 12th House District for 18 years and rose to national prominence as the chief architect of the GOP’s historic 1997 balanced-budget deal with President Clinton — used to joke about dosing him with Ritalin. His speaking voice is a marble-mouthed Pittsburgh bark. It tends to be several notches louder than the prevailing level of conversation. When he is not speaking, which is not often, his lips flutter and frown, desperate to get back in the game. He starts to answer questions before you can finish asking them. Even his hair, a bristly clipper cut, looks perpetually on edge, as if it has just endured yet another night of tossing, turning, restless sleep.

“What’s that?” Kasich says to no one in particular.

He is staring at a large black poster, one of several lining the walls of the Statehouse’s main corridor. He unfolds his reading glasses. The whole thing — an antismoking advertisement — is covered with handwritten notecards from children who have been “touched by tobacco.”

Kasich leans closer. “Jim!” he says. “You gotta see this!” Kasich’s traveling press adviser trots over. A few seconds later, Kasich spies Tim Armstead, the speaker of the West Virginia House. “Speaker!” he shouts. “You should talk about that” — Kasich taps one of the cards — “in the House. You should talk about it on the floor. I’m so touched by this. I mean, God — these children, they need us. We need to work on this.”

As Kasich and Armstead amble off together, I take a peek at the poster. I ask Kasich’s adviser which note got his boss so worked up. He points it out.

“My dad died of smoking,” it says in red marker. “I wish that didn’t happen.”

Suddenly, Kasich reappears behind me. “Did you see it?” he asks. I say yes. “It’s this one here,” he adds. Then he pauses to make sure I understand what I have witnessed. The note. The sadness of the note. The sadness of John Kasich as he notices the note.

“Isn’t that just tragic?” Kasich finally says. “I’m moved by these kids. I really am.”

I look up. His eyes are wet with tears.

***

John Kasich is convinced that he’s a different kind of Republican. “For some reason, the Lord has made me more aware of people’s problems,” Kasich told me in West Virginia. “And I take that awareness seriously.”

His mission now is to convince everybody else.

If you’re not from Ohio, or a political junkie, you probably haven’t heard much about Kasich. You may have heard nothing at all. His name rarely appears in the big 2016 rankings; he barely registers in the polls. A recent surveyshowed Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker leading the Republican pack with 18 percent of the vote. Jeb Bush followed closely with 16 percent. Chris Christie (8 percent), Mike Huckabee (8 percent), Ben Carson (7 percent), Ted Cruz (6 percent), Rand Paul (6 percent) and Marco Rubio (5 percent) rounded out the top tier. Kasich came in last with 1 percent.

But spend a few days with the governor, as I did recently in three different states, and you start to see how he could shake up the 2016 contest — if he decides to run.

Photo: Joshua A. Bickel for Yahoo News

The GOP is at a turning point. For the past six years, Washington Republicans have Just Said No — to Obama, to spending, to governing itself — without offering voters much of an alternative vision. But now what? Deficits are shrinking. Jobs are returning. The GOP controls both houses of Congress and stands a good chance of recapturing the White House. How should a Republican run, and lead, in postrecession, post-Obama America?

The Scott Walker model — crushing the unions, opposing immigration reform, rejecting Medicaid money, austerity above all else — will always appeal to the GOP base. But it may be too 2010 for 2016: a hard-right roadmap that would scare off swing voters and prove impossible for any president to implement.

Then there’s Kasich. Like his fellow Midwesterner, the governor swept into office on a wave of anti-Washington sentiment. “I was in the tea party before there was a tea party!” he said in 2010. He even tried to hobble Ohio’s public-sector unions — again, like Walker.

But while Walker famously won that battle, Kasich lost, and ever since he’s been charting a more idiosyncratic course. Ask him about climate change, and he admits that “we have to pay attention to science” because “it’s a real concern.” Ask him about a pathway to citizenship for illegal immigrants, and he confesses that “if at the end of the day that needs to be part of the solution, I’d probably be fine with it.” Ask him about Common Core — the Obama administration’s push for national education standards — and he chides his fellow conservatives for refusing to participate. “I don’t know how anybody can disagree with that,” he said on Fox News recently. “Unless you’re running for something.”

In Ohio, Kasich has stuck to his skinflint roots by eliminating the estate tax, tightening food-stamp requirements and championing business deregulation. But he has also raised infrastructure spending. And floated a fracking tax. And increased funding for mental-health care. And mandated insurance coverage for autism. He has even accepted Obamacare money to expand Medicaid coverage, enraging the tea party foot soldiers who propelled him into office.

The difference, according to Kasich, is simple. “I see economic development as a means to an end and not an end unto itself,” he told me. The ultimate goal, he added, is “helping those who can’t help themselves.” Or as Kasich put it in 2013, “When you die and get to the meeting with St. Peter, he’s probably not going to ask you much about what you did about keeping government small. But he’s going to ask you what you did for the poor.”

If this sounds familiar, Christian rhetoric and all, that’s because it is. Fifteen years ago, George W. Bush steered the GOP out of a similar dead end — Newt Gingrich, the shutdown, impeachment — by branding himself a compassionate conservative. “It is compassionate to actively help our fellow citizens in need,” Bush argued at the time. “It is conservative to insist on responsibility and results.” His brother Jeb is now saying a lot of the same things.

Photo: Joshua A. Bickel for Yahoo News

Kasich was an early fan of the concept. After exploring a 2000 presidential bid of his own, he reluctantly bowed to Bush’s fundraising prowess — and conceded that “George Bush’s term of ‘compassionate conservative’ really kind of defines what John Kasich is all about.”

Like many Republicans, Kasich eventually soured on Bushism, in part because Bush wasn’t conservative enough on spending. When Kasich retired from his role as House budget chairman and left Washington in 2001, the Congressional Budget Office was projecting a decade of surpluses ahead — $5.9 trillion in all. “The Republican White House was instrumental in spending that $5 trillion,” Kasich said during his balanced-budget speech in West Virginia. “And even a lot more.”

But the real bet Kasich is making in Ohio — the bet he would be making if he ran for president — is that he can do compassion better than Bush, too. “The old way” — compassionate conservatism 1.0 — “would have been going into a prison and talking to inmates or praying with them or whatever,” he told me. “A ‘woe is us’ kind of thing. But in Ohio, we’re innovating our prison system.” (Kasich has implemented policies that help inmates reintegrate into their communities; he also wants to reduce mandatory minimum sentences.) “I believe you can solve more problems — probably with less money — if you apply your resources more effectively.” This is where Kasich differs from Walker & Co. His gospel doesn’t stop with spending cuts. He wants conservatives to finally walk the walk on social welfare, too.

It’s a forward-looking but still fundamentally conservative message that might make more sense in 2016 — and beyond — than tea party talking points and reactionary red meat. There’s a reason, after all, why Jeb has now taken to calling himself an “inclusive conservative.” But what if the right messenger for the moment wasn’t burdened with a lot of Bush family baggage? What if he hadn’t been making money on Wall Street for the entire Obama presidency, but had been implementing his reforms instead? And what if he were just re-elected — by more than 30 percentage points — in the one state Republicans absolutely can’t afford to lose on Election Day? (No Republican has ever won the White House without winning Ohio.)

Could John Kasich — provocative, self-important and more than a little abrasive — actually be the GOP’s secret weapon?

At least John Kasich thinks so.

***

A few weeks after leaving West Virginia, Kasich invites me to spend the day with him in Columbus, Ohio. He turns out to be the least inhibited politician I’ve ever encountered. That little internal regulator that keeps most elected officials from saying anything even remotely impolitic? If Kasich has one, he proudly ignores it.

Photo: Joshua A. Bickel for Yahoo News

Take immigration. “I don’t really favor a path to citizenship, but I’m not taking it off the table,” Kasich tells me. “I don’t really favor people jumping the line, but I don’t know at the end of the day that it won’t be necessary in some form.”

“So if you run for president, you won’t start yelling ‘No amnesty!’ all of a sudden?” I ask.

“Haven’t you figured this out yet?” Kasich snaps. He leans forward in his seat.

“A lot of Republicans do.”

“But it’s not what I think!” Kasich shouts. “I think the border definitely needs to be improved. But I voted for amnesty once, and that was something Ronald Reagan proposed. People don’t know that. That would just scare the living daylights out of some people — that Saint Reagan was for amnesty!”

I’d say that Kasich is never happier than when he’s playing the contrarian, except that he may enjoy extolling his own virtues even more. For hours we sit in the governor’s lofty and largely ceremonial office — it’s the room where Abraham Lincoln learned he’d won the election of 1860 — and discuss his life, his faith, his politics and his future plans. He also lets me eavesdrop on his meetings (budget, education, cabinet and so on). What it all amounts to, by design, is The Case for Kasich, according to the world’s foremost expert on the subject.

Kasich was born in 1952 in McKees Rocks, Pa. — or “the Rocks,” as locals like to say. His father was a mailman. These two facts figure prominently in almost every public remark Kasich makes. McKees Rocks is a hilltop steel town on the western rim of Pittsburgh; in the 1950s and 1960s, it was full of big blue-collar families, and John Sr. knew all of them. Six days a week, he would leave his two-story brick house on Elizabeth Street at dawn to walk the neighborhood. “Everybody loved Mr. Kasich,” the governor’s childhood friend David Cercone told the Cleveland Plain Dealer last year. “He was the type of guy who if you wanted to mail a letter but didn’t have a stamp, you could tape a nickel on it and he would put a stamp on it once he got back to the post office.”

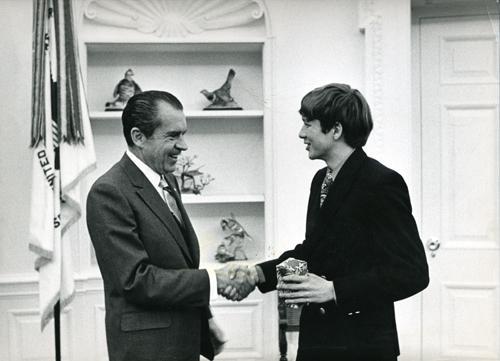

John Kasich meets with President Richard Nixon in the Oval Office in 1970. (Photo: Courtesy of the White House)

Kasich inherited his father’s gregarious nature. But his trademark restlessness came from his mother, Anne. “My mom was always thinking about the ways things could be better,” Kasich tells me. “She was highly opinionated and very smart. And she did not have a lot of regard for politicians.”

Even as a kid, Kasich was in a hurry. “As a smaller guy, I always had to give it everything,” he once explained. When the Pittsburgh Pirates won the World Series in 1960, an 8-year-old Kasich elbowed his way through the raucous celebration downtown to get his baseball signed by Bill Mazeroski, whose ninth-inning homer had toppled the Yankees. He was so devoted to his altar-boy duties at Mother of Sorrows Church that his friends dubbed him The Pope.

Before long, Kasich began to channel his ambition and assertiveness into politics. Both of his parents were Democrats, but from the start, John Jr. leaned right. “The problem is that I’ve never been a fan of rules, of orders, of red tape,” he tells me in his office. “And I always felt that the party of individuality was the Republican Party.” Once, Anne heard an articulate young conservative making his case on a local radio show. Thinking her son would appreciate the kid’s views, Anne hollered for him to switch on the radio. “Then she burst into her bedroom,” Kasich recounted in his 2006 book Stand for Something, “only to find me on the upstairs phone, doing the sounding off.”

During his first semester at Ohio State University, Kasich was so aggravated by a dorm rule that required every resident to chip in for a broken window — even those who didn’t break it — that he spent three weeks demanding an audience with university president Novice Fawcett. When they finally met, legend goes, Fawcett let it slip that he would be visiting President Richard Nixon in Washington, D.C., the next day. Can I come? Kasich asked. Flabbergasted, Fawcett said no. Then how about delivering a letter? Kasich continued. Fawcett relented. In the note, Kasich offered to “make [him]self available,” should Nixon ever require the counsel of an 18-year-old undergraduate from Ohio — and amazingly, Nixon accepted. For 20 minutes on Dec. 22, 1970, Kasich huddled with the leader of the free world in the Oval Office.

Kasich was hooked. After graduating, he served as an aide to an Ohio state senator, but — surprise, surprise — he couldn’t bear working behind the scenes. “I began to think, ‘When I develop an idea, I can present it as well as the people I’m giving this stuff to,’” Kasich says. “So I quit my job and ran for the state senate myself.” He was such a “persistent campaigner,” according to former state Rep. Jo Ann Davidson, a longtime Kasich ally, that “people said, ‘If you just quit calling me, I’ll support you.’” Kasich won the seat by 11,000 votes. He was 26 — the youngest member ever elected to the Ohio Senate. Kasich’s first marriage soon fell apart; he later confessed to “neglect[ing]” his college sweetheart because he was “too busy trying to get a toehold in the legislature.” And yet in 1982, after only three years in Columbus, he decided to run for the U.S. House and became the sole Republican challenger of the cycle to defeat a Democratic incumbent.

In Congress, Kasich’s “eternal restlessness did not sit well with some veterans in his party,” write David Maraniss and Michael Weisskopf in “Tell Newt to Shut Up!”, their history of the Gingrich years. As a result, Kasich was “known as a lone wolf, better at challenging authority than at negotiating.” Even though he was a devout conservative, Kasich never really cottoned to the GOP’s country-club image. His politics were more populist than plutocratic. “Growing up, the people in my neighborhood didn’t have a lot of control over their own lives,” he tells me in Columbus. “Anything big, whether it’s business or government, tends to stomp on people.”

So Kasich began to bombard the institutions that had gotten too big for his liking, even if that meant pestering his fellow Republicans in the process. He infuriated then-Defense Secretary Dick Cheney by partnering with a liberal Democrat, Rep. Ron Dellums of California, to cut back — and nearly kill — the Pentagon’sexorbitant B-2 bomber. (Cheney “to this day despises me,” Kasich boasts in Stand for Something.) He irritated Wall Street conservatives by calling on Congress to “end welfare as we know it… for corporations.” (“I’m really concerned about the growing difference between rich and poor in this country, the stagnating wages,” Kasich said in 1997 — 17 years before income inequality became a trendy talking point among Republicans.)

But what exercised Kasich most was deficits. He first touted a federal balanced-budget amendment as a young state senator, and he became more hawkish only after arriving in Washington. In 1989, Kasich finally decided to write his own budget. It received 30 votes, “an event too insignificant,”quipped Joe Klein in The New Yorker, “to be considered a fiasco.”

In 1997, Kasich (second from right), then the House Budget Committee chairman, applauds President Bill Clinton as he signs legislation aimed at balancing the budget and giving Americans $95 billion in tax cuts. (Photo: Reuters)

And yet the young congressman did the same thing the next year, and the next, and by 1991, the House — still dominated by Democrats — was awarding Kasich’s plan more votes than President George H.W. Bush’s. In 1993, Gingrich made Kasich the ranking Republican on the House Budget Committee even though he was seventh in seniority at the time, and when the GOP took over Congress the following year, Kasich took over the budget. Gingrich encouraged his lieutenant to upend the usual process and suggest specific, often excruciating, cuts to his colleague’s pet programs. Kasich’s tireless campaign eventually succeeded, and, with President Clinton’s signature in early 1998, the federal government adopted its first balanced budget since Neil Armstrong walked on the moon.

I ask Kasich how much credit he deserves for the surpluses that followed. “I spent 10 years of my life fighting to get there,” he says. “I was extremely involved.”

But soon he was no longer fighting — and no longer involved, at least not on Capitol Hill. When Kasich’s ninth term was up in 2001, he retired and returned to Columbus to spend more time with his second wife, Karen, and their twin daughters, Emma and Reese.

***

To describe a period in a politician’s life as The Wilderness Years suggests that he went off and hibernated. But Kasich, then only 48, could never sit still long enough for that. By the time he left Congress, he’d already lined up a pair of prominent gigs: one at Lehman Brothers and another at Fox News.

Kasich was a natural on Fox. As a congressman, he had guest-hosted for Bill O’Reilly and even Chris Matthews on occasion, and his Fox show, From the Heartland With John Kasich, which aired live from Columbus every Saturday night, blended O’Reilly’s hair-trigger sense of cultural outrage with Matthews’ brute-force approach to political debate.

But Lehman Brothers? That seemed out of character for someone with Kasich’s blue-collar outlook — even to Kasich. So why did he sign up? “I can’t give you a really good answer,” he says. “I thought I wanted to do something on Wall Street.”

Money may have been part of it. Kasich had a young family to support, and being a former congressman is lucrative; Lehman paid him a handsome $614,892 in 2008. But it’s also clear that Kasich liked the challenge of learning a new skill. “The first thing I told them is that ‘I’m not showing you my Rolodex, and secondly, I don’t want to talk about politics and I’m not going to go to Washington,’” he explains. “I think it was in my contract. I said, ‘I really want to learn the business, and I want to be a banker.’” Kasich was so enthusiastic, he took his Series 7 (the multihour test that everyone in the securities industry must pass) and called Lehman CEO Dick Fuld (who later became the big villain of the 2008 crash) “an awesome guy.”

Kasich after participating in the World Championship Sled Dog Derby awards in 1999 (Photo: Joel Page/AP)

As a managing director in Lehman’s investment banking division, Kasich operated out of a two-person office in Columbus that dealt with dozens of clients, including Silicon Valley investors and Midwestern steel magnates. Kasich’s relationships with the founders of Google — “Sergey and Larry,” as he likes to call them — helped Lehman get a small piece of the company’s 2004 initial public offering. When Democrats pounced in the wake of the crash, calling Kasich the “Congressman from Wall Street” and pointing out that Ohio’s public funds lost hundreds of millions of dollars on Lehman products, Kasich didn’t back down. “It was my most significant experience,” he said in a previously unpublished 2011 interview. “It’s one thing to be in office and to talk theoretically about job creation, but when you’re a banker and you’re out there meeting with CEOs and trying to convince them that you want to take them public, now you’re committed.”

By the time Lehman imploded, however, Kasich had already plotted out his next move. In February 2007, a mere month after Democratic Gov. Ted Strickland took office in Ohio, Kasich told The Columbus Dispatch, “I hope that [he] will do a good job so I won’t have to go around the state doing this stuff.” Evidently, Kasich wasn’t impressed; he started assembling his team and writing a budget the following year. And when he finally emerged from exile, as Henry Gomezwrote last year in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, he “was more mad-as-hell than feel-your-pain. The guy who once railed against corporate welfare now slammed Strickland for not being business-friendly. The guy who once sought middle-ground with lawmakers now pushed a polarizing plan to phase out the state’s income tax.”

Kasich carried his confrontational tea-party tone into office after defeating Strickland by 2 percentage points in 2010. A few days after the election, he warned lobbyists, “If you’re not on the bus, we will run you over with the bus.” When a black Democrat offered to help him identify minority candidates for his all-white, mostly male Cabinet, Kasich snapped, “I don’t need your people.” (A spokesman later said Kasich was referring to Democrats, not African-Americans, but still.) And shortly after taking office, Kasich was caught on camera referring to a cop who had pulled him over as “ an idiot.” Repeatedly.

But Kasich’s biggest early misstep was Senate Bill 5, which sought to end collective bargaining for public-sector employees. “They’ve got good jobs, they’ve got high pay, they get good benefits, a great retirement,” Kasich said before his swearing-in. “What are they striking for?” On March 31, 2011, he signed SB 5 into law — but it didn’t last long. Protesters swarmed the Statehouse. Kasich’s approval ratings plummeted; for most of the year, he was the most unpopular governor in the country. Voters eventually overturned SB 5 at the ballot box by a staggering 62 percent to 38 percent margin.

Even more shocking, however, was what happened next: the combative Kasich conceded defeat. “The people of Ohio have spoken,” he said on election night. “I respect their decision.” And then, miraculously, he moved on.

Kasich holds up a Lego figure during a news conference on March 6 at the Ohio Statehouse. (Photo: Joshua A. Bickel for Yahoo News)

“Frankly the legislation got too carried away,” Kasich admits today. “So I took a pounding on that. As a change agent, you’re going to have wins and you’re going to losses. And that was a loss, so I said I lost. I tried to take it like a man.”

Over the next few years, Kasich gradually found his comfort zone. Some observers claim the governor has moderated his views. But that’s not quite right. Kasich sees it more as a matter of “balance” — of finding ways to implement a governing philosophy that was always more idiosyncratic than his initial tea party image implied.

Many of Kasich’s policies are straight-up conservative, as any Ohio Democrat will tell you. He has signed legislation that makes itmore difficult for women to get abortions. He hasenacted limits on early voting . He has privatized the state’s economic development agency and sold off one of its prisons. And he has pushed for — and successfully passed — some of the largest tax cuts in the country.

But just as often, the governor’s plans are “pleasingly difficult to locate on an ideological map,” as conservative commentator (and former Bushie) Michael Gerson recently put it — the eclectic byproducts of Kasich’s “twin passions for economic growth and social inclusion.” His income tax cuts, for example, are paired with proposals to hike taxes on consumption (the state sales tax, the cigarette tax) and certain kinds of big business (the commercial-activities tax, the severance tax on oil and gas). At the same time, Kasich has increased state spending on an array of social issues — mental health, autism, addiction, recidivism — while pushing to transform the welfare system into a more “people-centered” one-stop shop that’s better at connecting Ohioans with jobs.

Perhaps the clearest example of Kasich’s undogmatic approach, however, was Medicaid. Many Republican governors, especially those mulling presidential bids in 2016, refused to accept Obamacare money to expand health services for the poor. So did Ohio’s Republican legislature. But for Kasich, who had reduced Medicaid spending earlier in his term, it was a no-brainer. “We talked for maybe a minute and the governor said, ‘We are doing this,’” recalls Ohio Medicaid Director John McCarthy. “He said, ‘You’re telling me that we can cover 375,000 people and get them behavioral health services and addiction services and it won’t cost us anything? And we’ll have two billion extra dollars to serve them?’ I said yes. And he said, ‘Why would I not do this?’”

A few days before I arrived in Ohio, Sen. Rand Paul — a near-certain candidate for the Republican nomination — came to the state and called Kasich’s decision to expand Medicaid “a mistake,” claiming that the U.S. would “have to borrow money from China” to fund the program. When I mention Paul’s remarks to Kasich, his eyes widen.

“Wait, so was it Rand Paul or Ron Paul?” Kasich asks me.

“Rand,” I reply.

“Oh, OK,” he continues. “Well, first of all, I’m not going to get into Ron Paul.”

I correct him again.

“Whatever,” he snaps. “Same difference. Here’s the deal. It’s our money. We’re bringing it back. We have severe problems with drugs, mental illness and the working poor. We can let them walk around like scattered sheep and end up in our prisons and our jails and our emergency rooms, sicker. That’s worse for them and more expensive for Ohio. And so I believe we have to get them the help they need.”

Suddenly, Kasich pauses. “Which guy are we talking about again?” he asks. “Rand or Ron?”

“Rand,” I repeat.

“And he’s from where?”

“Kentucky.”

Kasich at the Ohio State Fair in 2014 (Photo: Jay LaPrete/AP)

“And do they have problems down there?” Kasich says. “Maybe they don’t have problems. Well, we have problems in Ohio! And we’re fixing them!”

Kasich’s voice is rising with every syllable. He’s on a roll now. “Any of these people who say they’re so concerned about balancing the budget — let me see their budget plan!” he shouts. “They want to show us exactly what they’re going to do? With Medicaid? Medicare? Social Security? Or are they going to go hide?”

With that, Kasich settles back into his chair. “It’s easy to sit in the stands and criticize,” he concludes. “It’s a lot harder when you have to solve problems.”

I can’t help but notice that the governor is starting to sound a lot like a 2016 combatant himself.

***

Kasich, of course, ran for president once before. It did not go well.

At the time, in 1998 and 1999, Kasich was in his mid-40s, with a caffeinated demeanor and a floppy haircut that made him seem at least a decade younger. In Washington, he was known as the congressman who wore Sesame Street ties andonce got ejected from a Grateful Dead concert after attempting to stride onstage. Kasich tried to make his youthful reputation an asset on the trail, describing himself as the Jolt Cola to George W. Bush’s Coke and Elizabeth Dole’s Pepsi and warning prospective volunteers, “If you don’t want to have fun… go work for one of those fuddy-duddies, because we may have to go get a beer every once in awhile.” His love of Pearl Jam was widely publicized. But voters in New Hampshire and Iowa weren’t convinced — and neither were GOP donors. In the first quarter of 1999, Kasich raised less than $2 million. Bush raked in nearly 20 times that much.

“I thought I could change the world,” Kasich tells me today. “The message I got when I traveled around was, ‘We like you, but could you come back when you’re older?’”

Kasich has never been shy about his White House ambitions. In college, he used to introduce himself by telling people that he would be president someday. “My ambition … might have been a bit premature, and perhaps even a couple inches out of reach, but it was certainly genuine,” he writes in Stand for Something. “And so I set about it.” After Kasich conceded to Bush in 1999, he insisted in an interview with The Washington Post that he was “not giving up [his] dream of being president”; a year later, he told The Columbus Dispatch, “I will run for president again.”

So why 2016?

“My faith is deeper,” he tells me. “I’ve studied more. I’ve got a family. I’ve got kids. I’ve matured. I’m wiser now.”

Kasich is right to think that he might have a better shot this time around. His faith is a real asset. As a kid in McKees Rocks, religion was “more of a rabbit’s foot,” he explains. But in 1987, a drunken driver slammed into his parents’ car as they were pulling out of the local Dairy Queen. Both died — and Kasich “went back to ground zero.”

“I wasn’t even sure God existed,” Kasich tells me. “So I went through the Bible and became a real pest. ‘How do I know God exists? How do I know he cares about me?’”

He emerged with a renewed connection to religion — and the self-confidence, unlike some Christian conservatives, not to “shove [his] faith down anybody’s throat,” as he puts it.

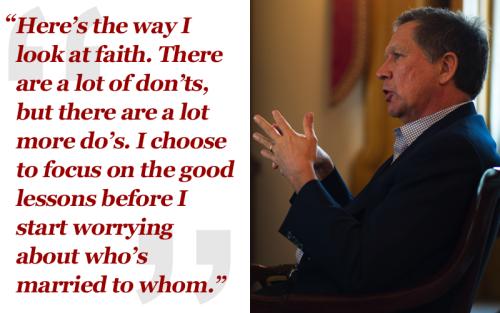

“Here’s the way I look at faith,” Kasich says. “There are a lot of don’ts, but there are a lot more do’s. Humility. Empathy. Love your neighbor as yourself. I choose to focus on the good lessons before I start worrying about who’s married to whom.”

Kasich at the Ohio Statehouse (Photo: Joshua A. Bickel for Yahoo News)

The governor’s record in Ohio is also an advantage. When Kasich took office in 2011, the Buckeye State was facing a projected budget deficit of $8 billion. Three hundred fifty-one thousand private-sector workers had lost their jobs in the recession, and the unemployment rate stood at 9.1 percent — the same as the national number. Now the picture is reversed: an unemployment rate (5.1 percent) that’s lower than the national average, a surplus of $800 million, and 352,000 private-sector jobs added over the last four years. Experts debate how much credit Kasich deserves for these developments, but like any politician in his position, the governor likes to claim most of it for himself. “We balanced budgets, cut taxes and prepared the workforce,” he insists during our interview. “There’s no question that we did a lot to create a good environment in the state.”

The majority of Ohioans seem pleased (even if progressives and tea-party types tend to object). In 2014, Kasich secured re-election by more than 30 percentage points, winning a majority of union voters, three-fifths of female voters, a majority of voters younger than 30, two-thirds of independents, and a quarter of African-Americans. It helped that his Democratic opponent imploded, but even so, the results were remarkably lopsided for a swing state. Kasich’sapproval rating currently stands at 55 percent. Only 30 percent of Ohioans disapprove of his job performance.

So what is Kasich waiting for?

He won’t say, but my sense is Kasich still faces the same hurdles that stymied him in 2000 (and he knows it). The first is money. “If I can fix my fundraising problems,” he vowed in 2001, “I will run again.” Presumably that’s why the governor laced his speech to the Republican Jewish Coalition in Las Vegas last March with repeated first-name shoutouts to GOP megadonor Sheldon Adelson, who is rumored to be shopping for a “mainstream” Republican to bankroll in 2016. It’s probably why Kasich rushed to D.C. earlier this month for the big speech by Adelson pal Benjamin Netanyahu. And it may be why, in our interview, he finally decides to throw a few darts at likely Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton, blaming her for failing to persuade the president to be “more forceful” in the Middle East.

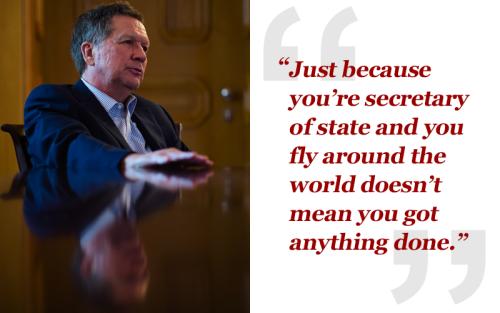

“Just because you’re secretary of state and you fly around the world doesn’t mean you got anything done,” Kasich tells me. “If Clinton was an advocate for more significant engagement, then why didn’t it happen? Does that mean she wasn’t very effective?”

Kasich’s second hurdle is Jeb Bush, who is currently cornering the market for compassionate conservatism just like his brother did in 2000. One minute, Kasich is telling me that “the situation is different” this time — that he’s a better communicator with a stronger resume who could challenge Bush’s establishment campaign with a maverick, McCain-like bid of his own. The next minute, he’s admitting, with a sad grin, that “it’s possible the situation will end up being very similar.”

“I don’t know,” Kasich sighs.

(Some insiders have speculated that Kasich is actually angling for the vice-presidential nod, and when I ask if he will rule that out, he demurs. “I intend to be governor if I don’t run for president,” is all he’ll say.)

In the meantime, Kasich will keep traveling: to New Hampshire, to Detroit, to South Carolina yet again. On Kasich’s first trip to the Palmetto State — his first visit to a key 2016 primary state after a long balanced-budget swing out west — I heard the governor say something that seemed to sum up the peril, and promise, of a potential Kasich campaign. Earlier, over the murmur of political gossip and the clinking of cocktail glasses, one state legislator told a reporter that he hadn’t “spent five minutes studying John Kasich”; another admitted that he knew “very little about him” as he bit into a complimentary chicken finger.

But now the floor of the Hilton’s Yellow Jessamine meeting room belonged to Kasich, and he opened it up to questions. The first came from a blond woman with a syrupy Southern accent.

“What’s your position on immigration?” she asked.

Kasich smiled. “Look, they always tell you when you go into states like South Carolina, you gotta be careful,” he said. “It’s never been my style to do that. I like to tell you what I think. We have to deal with the immigration problem in this country. We’ve got millions of people who have come over illegally, and it isn’t practical to think, in my opinion, that we can stick them on a school bus, drive them to the border, open the door, and say ‘Get out.’ So Republicans and Democrats have got to come together on a plan.

“So many of us are stuck on ideology,” he continued. “So many of us are trying to appeal to the loudest cheers in the crowd. That’s not how you do things. That’s not what leaders do. I’m not here just to be a Republican. I’m here to fix things and lift everybody. To give everybody a chance and everybody hope. If I’m not doing that, then why am I doing this at all?”

As the event wound down, I found Kasich’s questioner in the crowd. Her name was Sandra Bryan — a Bank of America retiree who joked that she now “talked trash” for a living. Bryan said she was leaning toward Walker for 2016 — she’d supported Rick Santorum in 2012 and “didn’t know anything” about Kasich — so I was surprised when she told me what she thought of the governor’s response.

“I was really impressed how he didn’t flinch,” she said. “He didn’t look down. He was ready with the answers.”

“Why did you think he might flinch?” I wondered.

“Well, some candidates do,” Bryan explained. “Because it’s such a hot topic. Many of them do want to respond to whoever’s shouting the loudest. But he didn’t seem to be like that. He wasn’t trying to impress anybody.”

“Do you think a candidate like Kasich could compete in a place like South Carolina?” I asked.

“Unfortunately, for a lot of strong conservatives right now, it’s my way or highway,” Bryan said. “But I have to tell you, I would consider him. I think he would resonate. And believe me, I’m a hard one to impress.”

Post a Comment